• Feature Story • 75th Anniversary

This story is part of a special 75th Anniversary series featuring the experiences of people living with mental illnesses. The opinions of the interviewees are their own and do not reflect the opinions of NIMH, NIH, HHS, or the federal government. This content may not be reused without permission. Please see NIMH’s copyright policy for more information.

Note: This feature article contains information and depictions of schizoaffective disorder (a mental illness characterized by symptoms similar to those of schizophrenia). If you or someone you know has a mental illness, is struggling emotionally, or has concerns about their mental health, there are ways to get help. If you are in crisis, call or text 988 to connect with the 988 Suicide Crisis Lifeline . To learn more about this disorder, visit NIMH’s schizophrenia health information page.

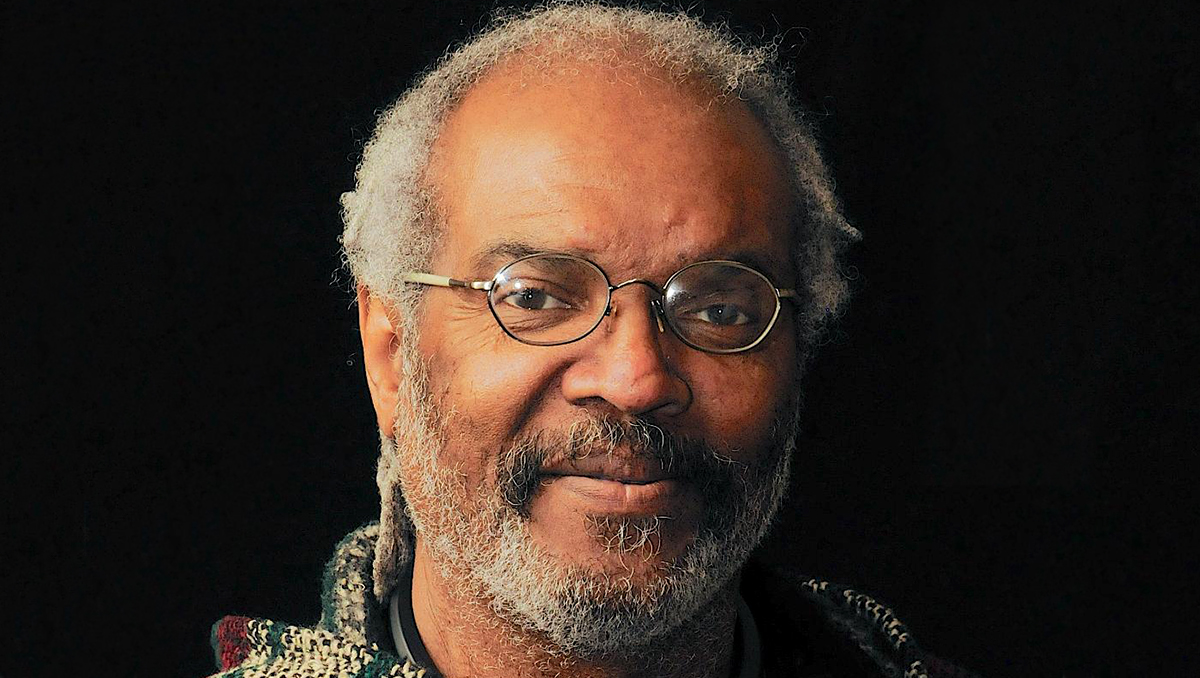

Everything about Ray Lay exudes positivity. He’s friendly, outgoing, and a role model.

But behind his gray beard and warm smile, there’s a story: part tragedy, part hope and redemption. Once a happy kid who used to help his father fix cars, everything changed on a fateful road trip in 1960.

The changes

Five-year-old Lay and his family were on a cross-country drive in Mississippi when they got into a car accident.

“The next thing I remember, I came to, and I’m looking down on the windshield. I’m seeing the blood, and I passed out again,” Lay said. “I woke up, and I’m in a man’s lap, in the ambulance.”

Slipping into a coma, Lay awoke 3 weeks later with more than 300 stitches. Once back in the schoolyard, his peers teased him.

“When I went to school, the kids—mean kids,” he recalled, “they used to call me Scarface.”

Lay didn’t know it then, but other changes were underway. He had begun talking to people who weren’t there. The first of these was Mel.

“When I woke up … after I went through the windshield, I saw my guardian angel, Mel,” Lay said. “He had white hair, white beard, dressed in all white, and as he would open his robe, he had snakes or worms in his chest. And I remember that part like it was yesterday. That was when he told me who he was and that he was there to protect me.”

To Lay, Mel was as real as a parent or teacher. And when he told Lay to do things, Lay listened.

At Mel’s urging, Lay began fighting the school bullies. Then, other kids. The rapid changes in his behavior left his father mystified.

“My daddy said I was the sweetest little boy,” Lay recalled. “And then, when I went through that windshield, he said, it was like the devil got in me.”

Childhood lost

At 7, Lay was expelled and shuffled to another school, where he routinely skipped class. By 8, authorities had sent him to a state juvenile detention center.

“I can’t say I was conflicted because, more likely than not, I probably didn’t even understand what that meant,” Lay said. “As far as the right or wrong, all the right was what Mel said to do.”

While they disciplined him often, Lay’s parents were quickly losing control of the situation. And though they brought him to see doctors, Lay said the treatments didn’t work.

Outside the home, he started fighting more, and stealing—first little things, then cars. Later, he joined a gang and quickly became mixed up in the violence.

One day, after being beaten by rivals, Mel insisted Lay act. Approaching the 20-year-old he thought led the attack, Lay took out a gun and shot him. The police later caught Lay and charged him with first-degree murder.

He was 15.

Into adulthood and confinement

It would take Lay decades to learn he has schizoaffective disorder. With this mental illness, symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations or delusions, occur at the same time as symptoms of a mood disorder, such as depression or mania.

Although Lay acted violently, most people with schizophrenia are not violent or dangerous, said Sarah Morris, Ph.D., Chief of the Adult Psychopathology and Psychosocial Interventions Research Branch at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

As Lay’s mental illness played a role in the shooting, the court found him incompetent to stand trial by reason of insanity. In hopes of providing the teen with treatment, the judge sentenced Lay to 2 years in a state maximum-security mental health facility.

While the measure had the potential to help, Lay said he had difficulties adjusting to the realities of long-term confinement. He also said that staff mistreated him and would tie him down, place him in straitjackets, or lock him in padded rooms.

Some of the ineffective and harmful practices of the past created a stigma for psychiatric treatment. Dr. Morris said that stigma still exists today and inhibits some people from getting the help they need. However, treatment for schizophrenia has improved since then, she added.

“There are many more medications now with better options for managing side effects,” she said. “Also, many clinics now use a coordinated specialty care approach, where teams of providers work together with patients and their families to provide care that includes psychotherapy, medication management, family education and support, service coordination, case management, and supported employment and education services.”

While mental health care has improved since then, Lay didn’t have the advantage of modern treatments for psychosis. His treatment at the maximum-security facility would remain unchanged, and through this process, facility staff shepherded Lay into adulthood.

Reentering the free world at 18, Lay dropped out of school and later joined the military. He thrived there for a few years, but was discharged after a psychotic break.

Without a purpose, Lay lost his way and embarked on a crime spree that ended after police arrested him for robbing a man of empty bottles. This time, there would be no insanity plea.

In considering Lay’s prior record, the judge sentenced Lay to 12 years in a maximum-security prison. He wouldn’t emerge from prison until he was 31.

Life on the streets

Once free, Lay sought to reinvent himself. He got married and moved to Indianapolis, which offered steady work. But remaining untreated, the symptoms of his mental illness never left.

“I was trying to make a life, but … I was a functioning drug addict and alcoholic with a mental health condition,” Lay said. “I was paying the bills, going to work, but I was messing up at work, I was messing up at home, and … I didn’t realize it then, but treatment is really what I needed.”

On the advice of his mother, Lay moved back to his hometown. But the situation was untenable.

Cycling between drug abuse and psychotic breaks, Lay became unhoused. Sometimes, he’d couch surf or burn through his disability checks to get off the streets, but mostly, he bounced in and out of homelessness.

He lived like that for 12 years.

While those close to him reached out, Lay denied his addictions. And though nearing 50, he still didn’t realize he had schizoaffective disorder.

“I didn’t accept it,” Lay said of his mental illness. “I felt … a sense of straddling the fence, with some hole in the role of me.”

Then, a chance encounter changed everything.

What is schizophrenia?

One day, while in a shelter, a clinical social worker approached Lay and asked if he was in treatment for schizophrenia.

“What is schizophrenia?” he asked.

The conversation opened doors, and for the first time in his life, Lay voluntarily enrolled in treatment. While other doctors had talked “at him,” this new one listened, allowing Lay to open up. In doing so, he began to heal.

“Do not be afraid to talk with a mental health provider—and I mean, talk,” he said. “Let them have your deepest, darkest so-called secrets, because I have found that giving mine away has helped me get a whole lot better.”

His psychiatrist prescribed medication, and this time, Lay stuck with it. Though adjusting to the side effects wasn’t easy, Lay said his desire to “live life” outweighed all else.

“While it might be initially frustrating, finding a treatment that works can have life-changing outcomes, especially if doctors catch the disorder early,” Dr. Morris said. “Modern treatment plans—developed with the patient’s input and goals in mind—help many people with schizophrenia and related disorders lead rich and fulfilling lives.”

As for Lay, therapy taught him how to work with his thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. In accepting his situation, his past, his challenges—everything started making sense.

Therapy also helped Lay get off drugs and alcohol. Recently, he marked 16 years of sobriety.

While he still faces challenges, he approaches them differently.

“I sometimes still talk to my voices, and when I do talk with them now, I know that they are not real,” he said. “But I realized that I need to keep taking my medication, stay away from illegal drugs and alcohol, and don’t miss none of my appointments: In other words, I need to stay in treatment.”

After making significant progress with his recovery, doctors felt Lay was ready to live a more independent life. In 2011, Lay took charge of his finances and secured an apartment, ending 12 years of homelessness.

Helping others

Between hospitalization, incarceration, and homelessness, Lay lost more than two decades of his life. Having missed out on so much, he tries to make up for it.

Lay began the new chapter of his life about 8 years ago, successfully running for a seat on the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), Indiana Board of Directors. He later earned a seat on NAMI’s national board, where he’s worked to further outreach about mental illnesses.

Lay also began working as a peer support specialist at the Department of Veterans Affairs, where he’s spent over 5,000 hours helping other veterans work through mental illness.

Now 68, while some people would be relaxing in retirement, Lay runs a business giving presentations on mental health.

“I get to take my sorrow, my pain, my hurt, my tears, and help others,” he said. “I get to go to some of the places I was incarcerated and hospitalized, and talk with some of the first responders and try to prepare them for what they might encounter.”

Much of his work seeks to bridge the gap of misunderstanding with law enforcement—his message: A little compassion goes a long way.

“I try to instill in the police that persons with mental health issues are still persons,” he said.

Recently, Ken Duckworth, M.D., Chief Medical Officer of NAMI, featured Lay in his book, “You Are Not Alone.” Reflecting on his journey with mental illness, Lay told Dr. Duckworth that helping people gives him purpose.

It’s his way, in part, of trying to forgive himself.

Through treatment, Lay’s become a better man. And for as long as he can, he wants to give back.

In reclaiming the kindness in his soul, Lay’s rediscovered who he was meant to be. He’s also now able to do something once unthinkable: connect with people.

He’s married to his wife, Dianna. They own a house in Indianapolis and care for their pet Chihuahua, Bentley.

He spends his days busy, optimistic, and trying to do good in the world.

It’s all he ever wanted.