Transnational security investigator Abdelkader Abderrahmane set out from the Moroccan city of Kenitra with two research assistants to inspect sand-mining sites on the Atlantic Ocean coast. They drove across the dry, flat terrain for six kilometers, the last stretch on a rutted dirt road that had them crawling in low gear, windows closed against the hot dust. The beach dunes where they were headed lay beyond a rise. As they approached, a man wearing a gendarme cap suddenly appeared to their right, speeding toward them on an all-terrain vehicle. With angry gestures, he forced them to a stop. “Why are you here?!” he demanded. “There’s nowhere to go.” One assistant said they just wanted to visit the beach and the nearby tourist camp. The gendarme shook his head: no further.

They turned around and began to creep back down the rough road, but as soon as the gendarme was out of sight they turned off and snuck along a hidden side of the ridge. About 400 meters further they stopped and cut the engine. Abderrahmane walked quietly to the crest of the bluff to peer down, keeping low to avoid being seen. Despite all his research into illegal sand mines, he was unprepared for the scene below. Half a dozen dump trucks scattered across a deeply pitted moonscape were filled high with brown sand. Just beyond lay the light blue sea. Abderrahmane was stunned by the “major disfiguration” of the dunes, he told me later on a video call. “It was a shock.”

Part of his shock came from the sight of desecrated nature, but part came from seeing the brazenness of trucks hauling sand in full daylight. “You cannot illegally mine sand in daylight if you don’t have people helping you,” he says—people in high places. “Big companies are being protected, perhaps by ministers or deputy ministers or whoever. It’s a whole system.” Everyone in the sand-trafficking market “benefits from it, from top to bottom.”

For the past 15 years the slender, bespectacled Abderrahmane has studied environmental trade and crime for the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), an African research and policy advisory organization based in South Africa. ISS papers showed how environmental degradation can fuel tensions among people and compromise security. But until a few years ago Abderrahmane had never heard of sand trafficking. He had been in Mali doing fieldwork on the drug trade when a source noted that most cannabis in Mali came from Morocco and that sand trafficking was also a major market in that country, with drug traffickers involved. “I think that when you talk about sand trafficking, most people would not believe it,” Abderrahmane says. “Me included. Now I do.”

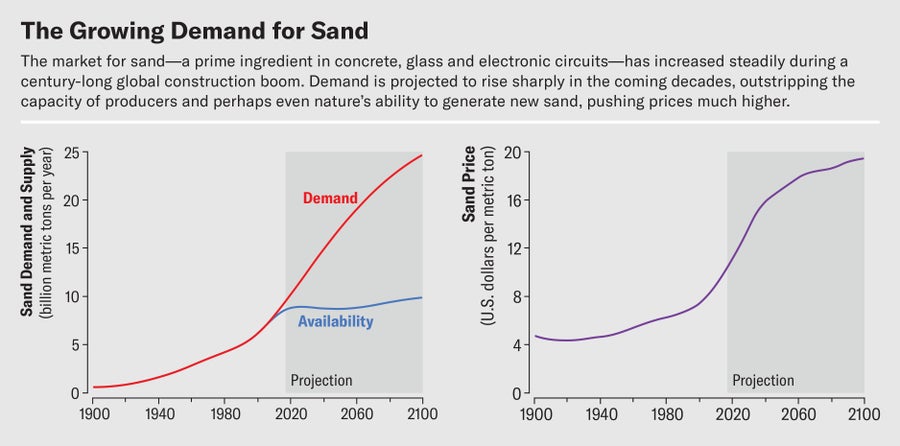

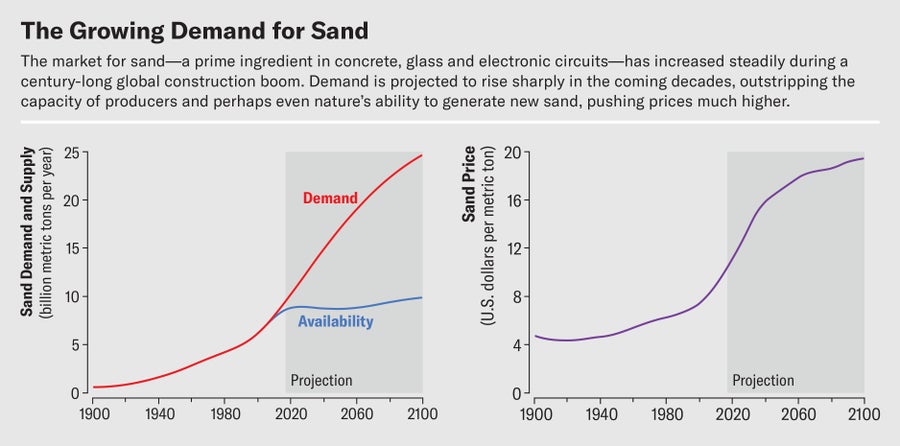

Very few people are looking closely at the illegal sand system or calling for changes, however, because sand is a mundane resource. Yet sand mining is the world’s largest extraction industry because sand is a main ingredient in concrete, and the global construction industry has been soaring for decades. Every year the world uses up to 50 billion metric tons of sand, according to a United Nations Environment Program report. The only natural resource more widely consumed is water. A 2022 study by researchers at the University of Amsterdam concluded that we are dredging river sand at rates that far outstrip nature’s ability to replace it, so much so that the world could run out of construction-grade sand by 2050. The U.N. report confirms that sand mining at current rates is unsustainable.

The greatest demand comes from China, which used more cement in three years (6.6 gigatons from 2011 through 2013) than the U.S. used in the entire 20th century (4.5 gigatons), notes Vince Beiser, author of The World in a Grain. Most sand gets used in the country where it is mined, but with some national supplies dwindling, imports reached $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Companies large and small dredge up sand from waterways and the ocean floor and transport it to wholesalers, construction firms and retailers. Even the legal sand trade is hard to track. Two experts estimate the global market at about $100 billion a year, yet the U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries indicates the value could be as high as $785 billion. Sand in riverbeds, lake beds and shorelines is the best for construction, but scarcity opens the market to less suitable sand from beaches and dunes, much of it scraped illegally and cheaply. With a shortage looming and prices rising, sand from Moroccan beaches and dunes is sold inside the country and is also shipped abroad, using organized crime’s extensive transport networks, Abderrahmane has found. More than half of Morocco’s sand is illegally mined, he says.

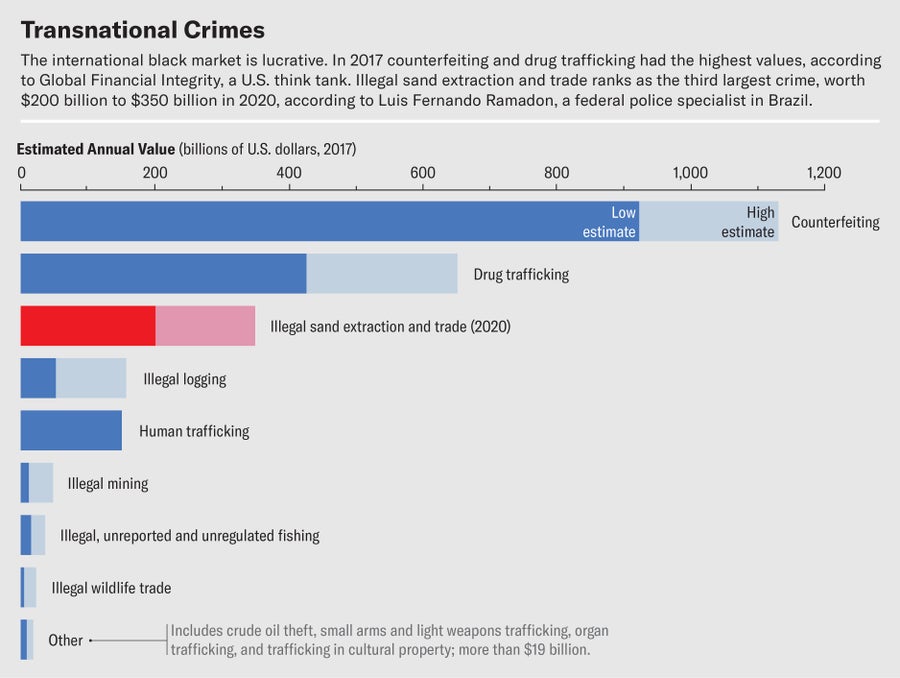

Luis Fernando Ramadon, a federal police specialist in Brazil who studies extractive industries, estimates that the global illegal sand trade ranges from $200 billion to $350 billion a year—more than illegal logging, gold mining and fishing combined. Buyers rarely check the provenance of sand; legal and black market sand look identical. Illegal mining rarely draws heat from law enforcement because it looks like legitimate mining—trucks, backhoes and shovels—there’s no property owner lodging complaints, and officials may be profiting. For crime syndicates, it’s easy money.

The environmental impacts are substantial. Dredging rivers destroys estuaries and habitats and exacerbates flooding. Scraping coastal ecosystems churns up vegetation, soil and seabeds and disrupts marine life. In some countries, illegal mining makes up a large portion of the total activity, and its environmental impacts are often worse than those of legitimate operators, Beiser says, all to build cities on the cheap.

Questionable mining happens worldwide. In the early 1990s in San Diego County, California, officials stopped mining from the San Luis Rey River, only to see operators move across the border into Baja California to plunder riverbeds there. Until a few years ago, a mine north of Monterey, Calif., operated by Cemex, a global construction company, was pulling more than 270,000 cubic meters of sand every year from the beach, operating in a legal gray zone. That was the last beach mine in the U.S., shut down in 2020 by grassroots pressure. Mining in rivers and deltas, however, is still going strong throughout the U.S., not all of it legal.

Sand is any hard, granular material—stones, shells, whatever—between 0.0625 and two millimeters in diameter. Fine-quality sand is used in glass, and still-finer grades appear in solar panels and silicon chips for electronics. Desert sand typically consists of grains rounded like tiny marbles from constant weathering. The best sand for construction, however, has angular grains, which helps concrete mixtures bind. River sand is preferable to coastal sand, partly because coastal sand has to be washed free of salt. But coastal sand does get used, especially when builders take shortcuts, leading to buildings that have shorter life spans and pose greater risks for inhabitants. Such shortcuts worsened the damage from the disastrous February 2023 earthquake that shook Turkey and Syria, says Mette Bendixen, a physical geographer at McGill University who has investigated the effects of sand mining since 2017.

I was first alerted to sand mafias by Louise Shelley, who leads the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at George Mason University. Shelley realized sand mining could be a natural evolution of organized crime when, five years ago, she was a guest at a NATO lunch conference held near the Pentagon. A top NATO official approached her to talk about illegal fishing off West Africa, saying it posed a serious threat to European and NATO security. They talked about how the low threshold for entry into an environmental crime such as wildlife poaching can draw criminal rings and then lead them into other types of organized environmental crime, such as illegal logging. Sand mining was another case in point. Shelley says in northwestern Africa there is a confluence of trafficking factors: the region offers entry to European markets, and its mosaic of fragile governments, terrorist groups and corrupt international corporations makes it vulnerable.

In addition to social instability, Shelley is concerned about sand mining’s “devastating environmental impacts.” Stripping away sand removes nature’s physical system for holding water, with huge effects for people’s way of life. River sand acts like a sponge, helping to replenish the entire watershed after dry spells; if too much sand is removed, natural replenishment can no longer sustain the river, which aggravates water supply for people and leads to loss of vegetation and wildlife. Harvesting has removed so much sand from Asia’s Mekong Delta that the river system is drying up.

Removing sand from coasts makes land that already faces sea-level rise even more exposed. Abderrahmane saw this in Morocco when he drove north from Rabat to Larache, known as “the balcony of the Atlantic.” The town, which looks out over 50-meter-high cliffs toward the sea, is a hub of Morocco’s thriving fishing industry. A 2001 government document known as the Plan Azur proposed greater protection of nature in many places in the country scoured for sand, including Larache. But in his 2021 field research, Abderrahmane found that the dark sand and rock-strewn beach there was rife with mining. Teams of workers loaded up donkeys with saddle packs full of sand, leaving stony craters at the water’s edge. They goaded the donkeys up footpaths torn into the soft, steep bluffs to trucks waiting above to haul the illicit material to various concrete production sites.

In Mozambique, increasingly destructive flash flooding has hit the town of Nagonha, which lies on the Indian Ocean. Elders there told Amnesty International they can’t recall any comparable flooding in the past, before the Hainan Haiyu Mining Company started operations in 2011, harvesting sand and minerals such as ilmenite, titanium and zircon from the dunes. The company dumped leftover sand across a wide area, spreading it to make a level working surface, which buried existing vegetation and blocked drainage, according to an Amnesty International report.

The company’s procedures failed to comply with Mozambican law, changed the flow of fresh water and are blamed for making Nagonha more vulnerable to the flash floods that have partly destroyed it, Amnesty International reported. One flood washed 48 homes into the sea, slicing a channel through the dunes, leaving nearly 300 people homeless. One man described to Amnesty International how his family’s two-bedroom house vanished: “We felt the house collapsing, and we ran for our lives” as he saw their home “being dragged by the water.”

Sand looting is changing the hydrology of entire rivers. Halinishi Yusuf experienced this as a girl growing up in Kenya. She also witnessed mining’s violent excess and eventually helped to bring it under control.

Yusuf, now studying sand mining and river systems as a Ph.D. candidate at Newcastle University in England, was born in Makueni County, southeast of Nairobi. As a girl, she carried water from the river, and like most residents, her family relied on rain-fed farming to eke out a living. But seasonal rains became erratic as a result of several interconnected climate patterns, and local farming and jobs declined. As life got harder, residents turned to harvesting sand for the construction boom in Nairobi. It was an easy form of employment because no investment was required except a shovel. Yusuf went away for high school in the early 2000s, and when she visited home, she saw trucks parked in the riverbed, loading up. Residents worked as loaders, and vendors sold food to the crews. Any river or tributary was fair game: if it gathered sand, it was exploited, and it wasn’t illegal.

Yusuf didn’t connect the mining to environmental damage. “It was just sand, anyway,” she says about her outlook back then. And the trade pumped cash into the economy; the village “was vibrant,” Yusuf told me on a video call. But damage to river systems was becoming clear. Groundwater levels were sinking; riverbeds stripped of sand didn’t hold water and failed to refresh aquifers underground. Farmers already struggling couldn’t irrigate their crops. Social tensions grew heated. Under Kenya’s “devolution” of public services from the national government to the country’s 47 counties, local agencies took responsibility for sand-harvesting licenses, often without resources to manage it. The process was unregulated and soon overwhelmed.

To try to stop the chaos, Makueni County passed a law in 2015 creating a local sand authority. But from 2015 to 2017 violence over sand wracked the area, leaving at least nine people dead and dozens injured. Even legal actors operated clandestinely, and local governments exploited permit fees, Yusuf says. “No one was frowning on this activity.”

Other counties had similar conflicts, but in Makueni a small group of sand loaders changed course and became vigilantes. They realized that mining was worsening arid conditions and that only outsiders were profiting. They saw officials getting rich from bribes and construction teams hauling the county’s sand wealth elsewhere. The group vowed to stop trucks no matter what it took. It imposed its ban on trucks leaving the area by torching offenders. Late one December night in 2016 two Kenyan truck drivers met a horrible death when they were parked beside the Muooni River, loading sand right out of the riverbed after midnight. The vigilantes surrounded them and set the trucks on fire. Both drivers died, burned “beyond recognition,” police reported to local media.

Not all the local people wanted to stop the lucrative business, however, and two factions clashed, resulting in more deaths. The Nairobi transport network poured cash into the pro-mining faction. “The conflict was funded from outside by the sand cartel in Nairobi,” Yusuf says, and law enforcement failed to intervene.

The violence and damage to the rivers peaked in mid-2017, around when Yusuf left Nairobi, where she had been working on fisheries management. She returned home to lead the Makueni County Sand Authority, which had made little headway. When applying for the job, Yusuf made her soft skills a selling point. She said she would enforce the 2015 law but noted that “there’s a palatable way of making the community start appreciating why we need to do this.”

When she began the job, she called a morning meeting in Muooni with local stakeholders. The village administrator and elders spread the word. Several dozen people toting plastic chairs gathered at the Muooni River, where mining was rampant, and sat in the shade. Yusuf had rehearsed her spoken Kikamba, the local language. Although she had taken part in stakeholder meetings in her fisheries job, she had never led one like this. “The entire county is watching,” she thought at the time. “I have to bring it forward.”

Yusuf explained to her audience how sand supports water in dry areas and how water gets replenished. She said the sand was like a sponge that made water available for them and the ecosystem. “Where there is sand, there is water,” she told them. During the discussion residents became reassured that they could gain income from sand while also allowing it to recharge the water supply. Over the next five years, under Yusuf’s leadership, the sand authority gained trust. It prosecuted the worst offenders and imposed strict fines on illicit mining.

Yusuf’s strategy was threefold. First, she used government power to stop sand from leaving the county. The authority allowed permits only for local construction projects: no more trucks from Nairobi. Second, Yusuf continued a series of meetings with local groups at the rivers. Finally, she made her office’s books public and used that transparency to show that half the revenue from licensing fees went straight to river restoration projects. People aiming to flout the controls backed off. Shady syndicates from Nairobi no longer had effective local agents in Makueni and found it easier to source their sand elsewhere.

For the first time, sand revenues produced visible local benefits. Projects ranged from “sand dams”—concrete weirs across the riverbed that catch sand pushed downstream by the rains—to “water sumps,” concrete tanks sunk several meters below the riverbed, used to draw drinking water. Leaving riverbeds untouched for even one rainy season (Kenya has two rainy seasons a year) allowed upstream sediment to replenish the controlled withdrawals, according to Yusuf. The community saw that there could be a way of life beyond selling sand to outsiders.

Change is harder in places where local groups lack the power to manage resources. In Morocco, Abderrahmane found a wide range of people profiting from the clandestine system, from local workers to high officials. The few people who protested were intimidated. French documentarian Sophie Bontemps experienced this in 2021 when her crew was filming at dunes near El Jadida. Police arrested them for filming, Bontemps told me, interrogated them for a full day, and confiscated their equipment. That evening a military colonel working with two plainclothes officials arranged a mock trial in a hotel; near midnight they forced the crew members to sign a document in Arabic admitting they had no right to film and to erase their footage. Finally, they were released. (The team had saved the footage elsewhere.) To Bontemps, it was clear that national officials were involved in sand trafficking. Her film, Morocco: Raiding on the Sand, reports incidents of local protesters being threatened and beaten.

Abderrahmane was finding it difficult to clarify the range of corruption. Sand mined for nearby buildings might fly below the radar of local officials. But long-haul transport involving scores of trucks traveling long distances on a public highway could not escape notice. In Larache, he couldn’t count on government support, so he took a gamble. His team posed as real-estate developers seeking contractors for a big project in Casablanca, more than 200 kilometers south. At a compound where massive reddish sand piles signaled construction supply, one of Abderrahmane’s assistants entered through a corrugated metal gate late in the day, when trucks were back from deliveries. He made bidding inquiries for a fictitious building project. He was stunned by the response: bidders could mobilize hundreds of trucks and front-end loaders within a week. “That would be very easy,” one man told him.

On other days the assistant directly approached drivers of sand-laden trucks parked downtown. From the driver’s seat, one transporter explained that contractors could arrange night hauling with up to 250 trucks through a syndicate of firms. Once the sand got delivered, construction companies mixed trafficked sand with legal sources. The contractor’s confidence that they could deliver such volumes across great distances, requiring large loads to pass at least 10 highway checkpoints, indicated multiple layers of official collusion, Abderrahmane says.

Because local people often struggle to push back against big syndicates, international pressure can push governments to prosecute traffickers. In Morocco, a strategy would likely require stronger environmental regulations, promotion of sustainable practices and transnational enforcement. An international certification system akin to the Forest Stewardship Council’s process for timber sourcing is still only in the discussion phase, says Pascal Peduzzi of the U.N. Environment Program. But Abderrahmane’s Moroccan sources say the government might consider action if sites were certified by the Convention on Wetlands, an international process dating back to the 1970s and observed by most U.N. member countries. A country submits a list of wetlands for accreditation, and if the international body overseeing the convention grants it, the wetlands can be monitored by an independent advisory committee to help ensure the site is preserved and not plundered. New technology might help distinguish whether sand came from a legal or illegal operation; in 2023 researchers from several universities demonstrated an optical system that can fingerprint sand grains, allowing them to be traced back to their site of origin.

Before conservationist Rachel Carson created a narrative in the 20th century for water and air pollution in Silent Spring, the general public had little context for seeing streams or the sky as health threats. Journalist Beiser told me he thinks a similar situation exists for sand.

George Mason’s Shelley is encouraged by a new generation’s energy for the problem. When we spoke, she was reading student papers about illicit environmental trade, happy that many of the students are career professionals in agencies where they can make a difference. Often it takes fresh eyes to change things, and Yusuf and Abderrahmane may inspire other people who are concerned about the environment and abuse of local communities.

More research will help build cases against crime rings. The number of sand studies presented at the American Geophysical Union’s annual conference grew from two in 2018 to more than 20 in 2023, McGill’s Bendixen says. That research can eventually yield better mapping of sand flows, showing hotspots and illegal activity.

Bendixen was heartened that the African Futures Conference in 2023 devoted a special session to sand extraction. “The time is running out for sand,” she says. “More people from as many different angles as possible are shouting out to the world, ‘We have an issue!’ I think it’s one of the most understudied global challenges of the 21st century.”